-

The investigation of cold atoms and molecules constitutes a cornerstone in modern physical science, with profound implications spanning quantum simulation precision measurement and quantum-controlled chemistry [1−10]. It is critical to such studies of the development of robust cooling methodologies, particularly for polar species with employing Stark deceleration [11−13], Zeeman deceleration [14−16], photoassociation processes [17−22], and cryogenic cooling using He buffer gas [23]. Among these, buffer-gas cooling primarily utilizes collisions between atoms or molecules and cooling noble gases for energy transfer.

Chandler and colleagues have demonstrated the fundamental energy transfer processes for achieving the kinetic cooling of rotationally excited NO, which occurs through single collisions with argon at low collision energies ranging from 1.4 kcal/mol to 3.5 kcal/mol in crossed-beam experiments [24−26]. By employing comparable methodologies, they successfully achieved kinetic cooling of both rotational-state selected ND3 molecules and Kr atoms [27, 28]. In 2007, Liu and Loesch reported the generation of slow KBr molecules formed by exoergic reactive collisions in counterpropagating beams of K atoms and HBr molecules [29]. Additionally, Scherbul et al. performed calculations that indicated the potential of chemical reactions involving alkali-metal dimers for generating ultracold molecules in crossed beams [30]. The application of advanced molecular beam technology for kinematic cooling presents unique advantages, particularly for species that are not readily amenable to laser cooling, due to its state-selective and collision-energy-dependent thermalization efficiency.

In addition to investigations focused on molecules, there has been a growing interest in the cooling and trapping of non-S-state metal atoms, which are characterized by a nonzero orbital angular momentum quantum number (L≠0), such as aluminum and various transition metals [31, 32]. A primary challenge associated with the laser cooling of these non-S-state atoms is their complex electronic configurations, which result in multiple spin-orbit states. The presence of these diverse electronic states complicates the cooling process, rendering it more difficult to achieve the desired reductions in temperature using laser cooling techniques. Connolly et al. have suggested the viability of utilizing sympathetic cooling and magnetic trapping for Al(2P1/2) atoms [33]. In this regard, we present our research on the kinetic cooling of aluminum atoms achieved through crossed beam collisions. These collisions involve a superthermal aluminum beam and a supersonic O2 beam at relatively high collision energies. The superthermal aluminum beam, generated through laser ablation, allows for systematic investigations of kinematic cooling effects across a range of collision energies. These studies are enhanced by the application of velocity-resolved time-sliced ion velocity map imaging combined with state-resolved resonance-enhanced multiphoton ionization (REMPI) detection techniques [34, 35].

-

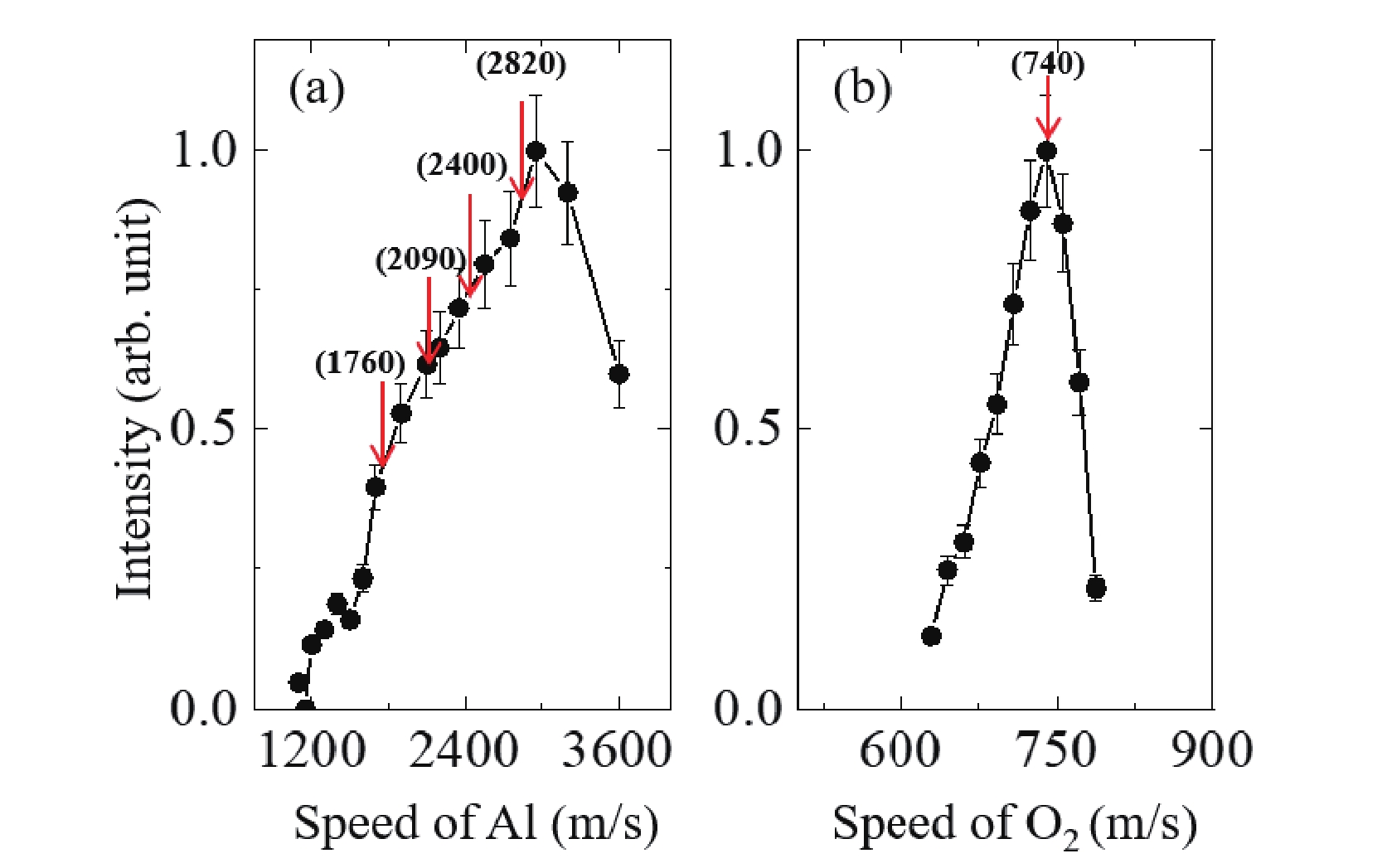

The experimental setup utilizing laser ablation in crossed molecular beams, along with the time-sliced ion velocity imaging technique, has been described in detail [36−40]. The vacuum apparatus is primarily divided into three distinct chambers: two source chambers responsible for generating the superthermal aluminum beam and the supersonic oxygen beam, and a single collision chamber designated for scattering studies. Each of these chambers is independently equipped with its own pumping system to maintain the required vacuum conditions. The superthermal aluminum atomic beam is generated through the laser ablation of an aluminum nitride (AlN) rod, utilizing a 532 nm laser with an energy output of approximately 6–8 mJ per pulse at a frequency of 15 Hz (Continuum Minilite II). The aluminum atoms are emitted directly into the reaction chamber without the use of a carrier gas. Two deflector plates serve the purpose of redirecting ions away from the aluminum beam before they enter the skimmer. One of the deflector plates is maintained at a voltage of 400 V, whereas the other is grounded, facilitating efficient ion deflection. The measured velocity of the superthermal Al beam produced by laser ablation ranges from 1200 m/s to 3600 m/s, as shown in FIG. 1(a). By varying the time delay of the ablation laser in relation to the detection laser, we can selectively obtain aluminum atoms with specific velocities, since this time delay represents the flight time of the aluminum atoms from the ablation point to the center of the crossed beam region. The higher speed of the Al beam, which exceeds the detection diameter of the MCP detector, is not represented in the figure. In contrast, the supersonic O2 molecular beam exhibits a peak speed distribution at 740 m/s, as shown in FIG. 1(b), which is generated using a pulsed Even-Lavie valve operating at a backing pressure of 14 atm. The supersonic Al atomic beam and the O2 molecular beam are collimated using a skimmer (Beam Dynamics Model No. 50, diameter 3 mm) and are directed to intersect at a right angle (90°) at the center of the ion optics assembly.

The scattered aluminum atoms in the Al(2P1/2) state that result from collisions with O2 are selectively ionized using (1 + 1) REMPI, employing the Al(2D) intermediate state at a wavelength of 308.30 nm. The ultraviolet (UV) laser employed for the REMPI scheme is produced by a narrow-band continuum sunlite OPO/OPA laser, which is pumped by the 355 nm output of a pulsed Nd:YAG laser with a pulse width of 5–9 ns and a pulse energy of 1–3 mJ. This UV laser is focused into the intersection region of the two molecular beams using a cylindrical lens with a focal length of 500 mm, positioned to bisect the beams and form a 45° angle with each. The ionized aluminum ions are subsequently accelerated through the ion optics towards an imaging detector. This detector is composed of two microchannel plates (MCPs) (75 mm diameter, 10 μm pore size, 12 μm pitch, from Photek) and a phosphor screen (P43, Photek). Time-sliced images of the aluminum ions are captured using a 30 ns gate pulse on the front MCP. Millions of laser shots are collected for each image. The Al+ background signals from the Al beam are effectively removed by alternately activating and deactivating the O2 beam, thereby mitigating their impact on the signals from the crossed-beam collisions.

-

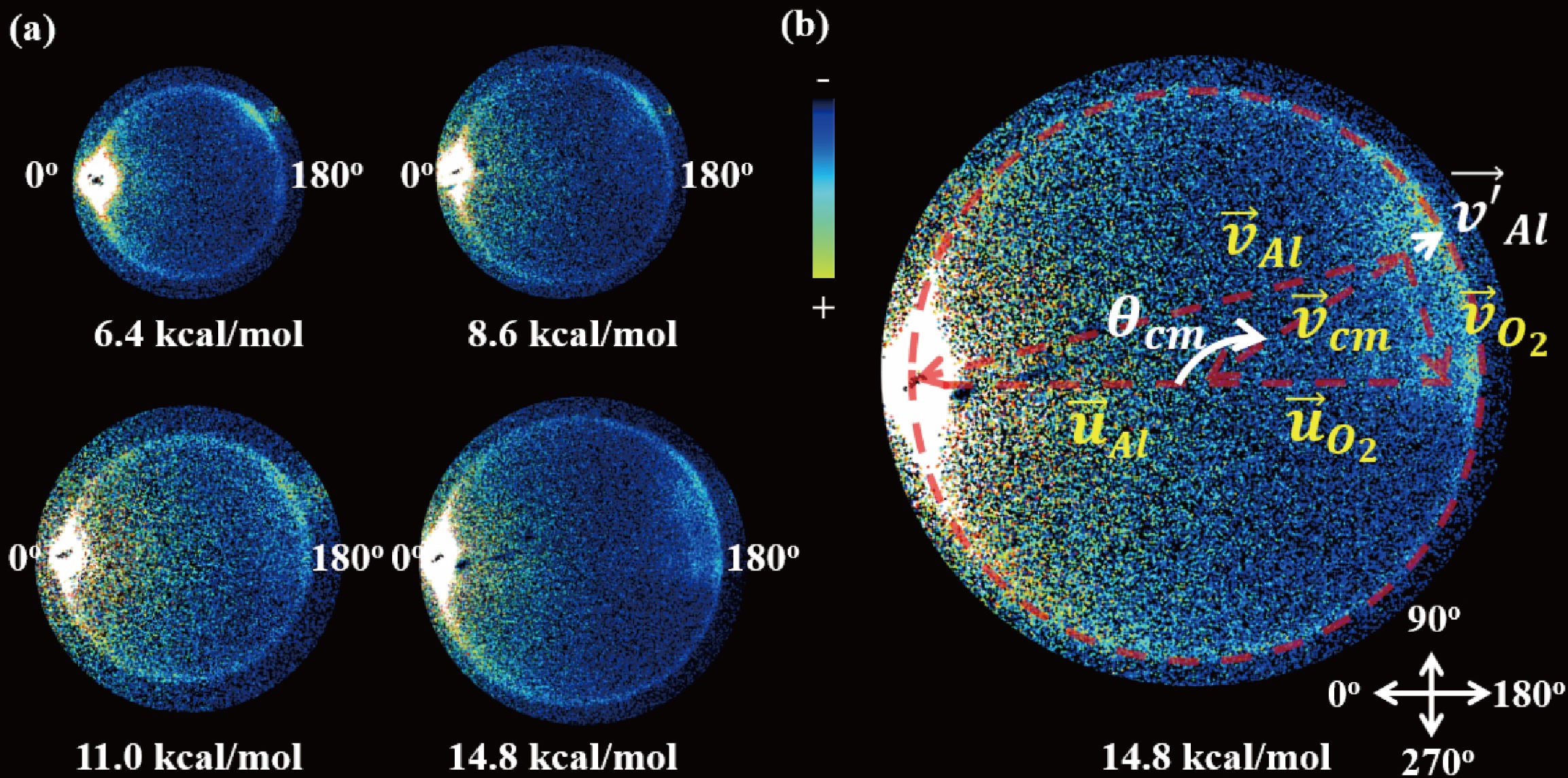

The state-selective sliced images of Al(2P1/2) obtained from the collision between Al atoms and O2 molecule at collision energy of Ec = 6.4±0.1, 8.6±0.1, 11.0±0.1, and 14.8±0.2 kcal/mol are presented in FIG. 2(a). These images were captured following background subtraction and depict the intersection of the O2 beam with the Al beam at various velocities within the crossing region. The edges of the images, shown in light blue, primarily represent the background at the signal cut-off location and do not correspond to the physical edges of the detector. In the center-of-mass (COM) coordinate system, the flying direction of the Al beam is defined as 0°. A similar angular distribution was observed across all collision energies in the range of 6.4–11.0 kcal/mol, characterized by strong forward scattering that extends into the sideways and backward directions. At the higher collision energy of 14.8 kcal/mol, notable strong backward scattering was observed, exhibiting multiple peaks that indicate the vibrational excitation of O2. Importantly, the strong signal is noted near the crossing position of the two beams, corresponding to low speeds of Al atoms in the lab frame. It can be understood that although the angular distributions are anticipated to be symmetric across the ranges of 0°–180° and 180°–360° from the forward to the backward direction, the scattering Al atoms with low laboratory velocity have a higher detection probability due to the density-to-flux transformation [41].

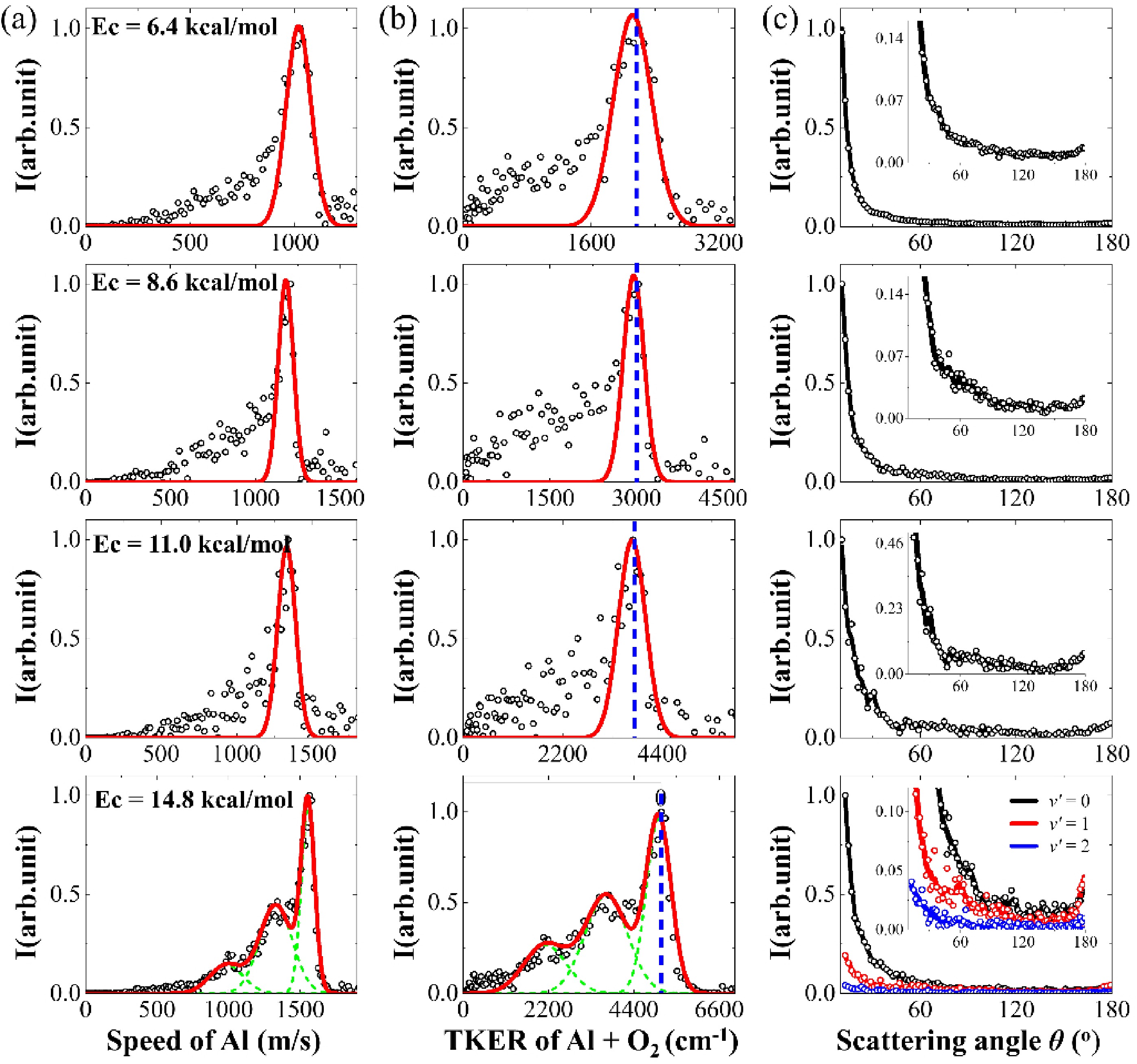

The speed distributions of the Al products were derived by integrating the signals from the images in the backward direction (180°±20°), allowing for a better resolution, and were transformed into the total kinetic energy release (TKER) distributions of Al and O2 reactants, in accordance with the principle of conservation of recoil momentum, as illustrated in FIG. 3 (a) and (b), respectively. At low collision energies, the velocity distribution of scattered Al atoms shows a strong background effect from the Al beam. This occurs because the density of slow-moving Al atoms is lower than that of fast-moving Al atoms during the beam expansion, as illustrated in FIG. 1(a). Consequently, the signal-to-noise ratio is poorer at low collision energies compared to high collision energies. In FIG. 3(b), the peaks of the TKER distributions for three low collision energies (Ec) of 6.4, 8.6, and 11.0 kcal/mol are observed at 2180, 3000, and 3790 cm−1, respectively, which align with the respective collision energies. At a higher collision energy of 14.8 kcal/mol, the kinetic energy distributions of Al and O2 present a series of peaks that are assigned to the vibrational excitation of O2 up to v' = 2 based on the conservation of energy. The spacing between adjacent peaks of ca. 1550 cm−1, as determined through Gaussian fits, aligns with the vibrational constant of O2 (ωe = 1580 cm−1) [42].

The angular distributions of scattering Al atoms in FIG. 3(c) were derived by integrating the Al atoms within a velocity range defined by the peak ± full width at half maximum (FWHM) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The forward angular distributions in the range θ = 0°–10° are omitted from the figure due to the substantial background from the Al beam, which could not be entirely eliminated even following background subtraction. The angular distribution of elastic scattering from Al atoms demonstrates pronounced forward scattering that extends to 180° across the collision energies of 6.4–14.8 kcal/mol. The strong forward scattering indicates a long-range attraction between Al and O2, as revealed in the theoretical calculations dominated by attractive dispersion forces in Al(2P1/2) and O2 approaching at large impact parameters [43]. In the previous work, we reported the reactive and nonreactive scattering in the collision of Al and O2 at low collision energies of Ec = 1.2 kcal/mol and 2.6 kcal/mol [38]. At lower collision energies, the angular distributions of Al(2P1/2) demonstrate a significant forward scattering pattern that extends up to 180°, with sideward and backward scattering exhibiting nearly isotropic characteristics. This observation implies the formation of transient complexes whose lifetimes are comparable to their rotational periods, ultimately leading to decay back into the reactants. In a similar vein, at collision energies between 6.4 and 11.0 kcal/mol, it is anticipated that the intermediate complexes will also be short-lived; however, they are expected to possess even shorter lifetimes, as evidenced by a diminished isotropic nature in sideward and backward scattering.

Notably, the backward scattering in the angular distribution of scattering Al atoms was observed at the high collision energy of 14.8 kcal/mol with the vibrational excitation of O2. This suggests that high speed leads to a short time in electron transfer, thus resulting in rebound collisions in direct scattering along the neutral surfaces of Al-O2.

From FIG. 2 and FIG. 3, it is clear that the Al atoms with the excited O2(

$ v' $ = 1) state have an almost zero speed in lab coordinate. The scattering angle for the cold scattering Al atoms is satisfied with the following equation [25, 26],where

${E}_{{\rm{O}}_{2}}$ and${E}_{\rm{Al}}$ are the initial kinetic energies of O2 and Al,${m}_{\rm{Al}}$ and${m}_{{\rm{O}}_{2}}$ are the masses of Al and O2, respectively. Meanwhile, the center-of mass velocity of Al atoms is given bywhere

$ M $ represents the total mass of${m}_{\rm{Al}}$ and${m}_{{\rm{O}}_{2}}$ . The velocity$\vec{u}'_{\rm{Al}}$ of the scattered Al atoms in the center-of-mass frame is given bywith

$E'_{\rm{int}}$ for the available internal energy of the scattered O2 molecules relative to O2 ($ v' $ = 0). In the context of elastic collision processes, the internal energy$E'_{\rm{int}}$ of the O2 molecule is zero. Comparatively, for vibrational excitation of O2 ($ v' $ = 1), the internal energy$E'_{\rm{int}}$ of O2 is 1553 cm−1. The laboratory-frame velocity of the Al atoms scattered along${\theta }_{\rm{cm}}$ is calculated according to:As the Al velocity in the laboratory frame

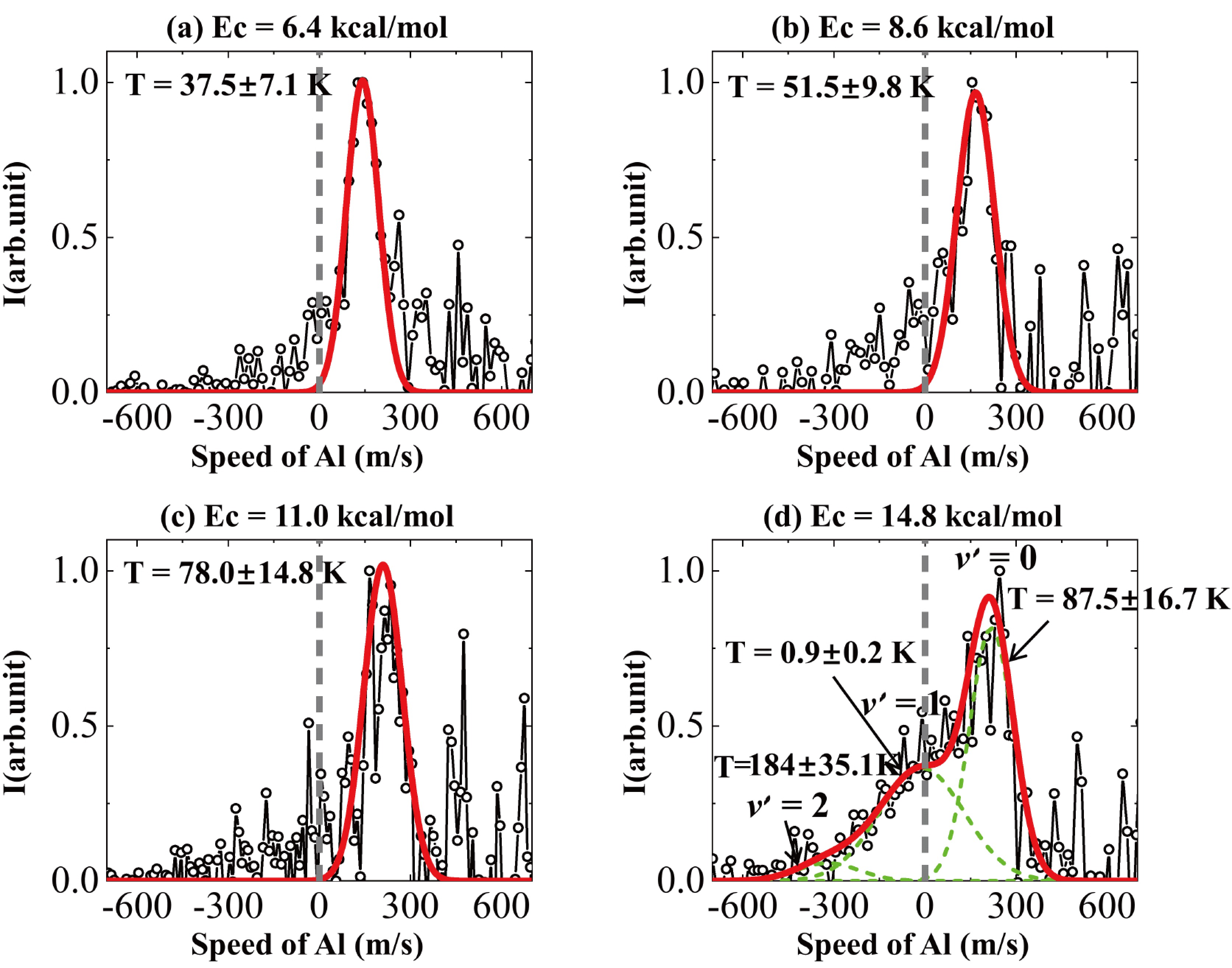

$\left|\vec{v}'_{\rm{Al}}\right|$ approaches to zero, a corresponding decrease in the kinetic energy of the Al atoms is anticipated. This phenomenon is depicted in FIG. 4, where a pronounced signal corresponding to the vibrational excitation of O2 ($ v' $ = 1) is observed for the slow Al atoms. The observed signal enhancement can be attributed to the high probability of the laser detection during the density-to-flux transformation [41].According to Eq.(1), the cold scattered Al atoms at the collision energies of Ec = 6.4, 8.6, 11.0, 14.8 kcal/mol in the laboratory frame correspond to center-of-mass scattering angles at

${\theta }_{\rm{cm}}=$ 130.3°, 137.8°, 142.8°, and 148.0°, respectively. The velocity distribution of Al atoms in the laboratory-frame along${\theta }_{\rm{cm}}$ are shown in FIG. 4. In determining the translational temperature (T) for the laboratory-frame velocity, we utilized the root mean square velocity derived from the speed distributions, based on the equation,$ \bar{E}_{{\mathrm{trans}}} = \displaystyle\frac{1}{2}mv_{\rm{RMS}}^2 = k_{\rm{B}}T $ [25], where${k}_{\rm{B}}$ is the Boltzmann constant. The translational temperature at various collision energies is illustrated in FIG. 4. It is clear that the elastic collisions between Al and O2 at higher collision energy lead to increased translational temperatures of the Al atoms in lab frame. Conversely, inelastic collisions that lead to vibrational excitation of O2 ($ v' $ = 1) at high collision energy of 14.8 kcal/mol result in slow Al atoms to sub-kelvin translational temperature, specifically 0.9±0.2 K.The findings and discussions presented herein provide significant insights into the cooling mechanisms exhibited by aluminum atoms during their interactions with oxygen molecules within the context of inelastic collision energy transfer. Our results bolster the idea that kinematic cooling is an effective approach for achieving velocity cooling in atom-molecule systems. Importantly, our measurements indicate an enhanced probability to the detection of slow-moving scattered Al atoms resulting from inelastic collisions, as evidenced by an increase in detection probability in density-to-flux transformation, a hallmark of effective translational cooling.

In our previous work, we utilized superthermal aluminum beams in investigations regarding the reactions and inelastic collision scattering between Al and CO2 at high tunable collision energies [44]. It was observed that elastic scattering of Al and CO2 predominantly occurred in the forward direction, with a notable absence of signal distribution in both sideways and backward scattering due to the formation of bent CO2− molecules during the electron transfer between Al and CO2. Furthermore, the McKendrick group employed superthermal aluminum beams as reactive probes to study fluorinated interfaces, successfully observing the generation of AlF products through superthermal collision reactions [45]. Currently, our research with superthermal Al beams demonstrates the generation of translationally colder Al atoms at the intersection of crossed beams due to vibrational excitation of O2 during collisions. These findings indicate that high-intensity and high-speed laser-ablation metal beams can play a significant role in achieving cooling and facilitating reactions involving various atoms and molecules. Further investigations into the cooling of atom-molecule systems will be elaborated upon in future studies.

-

In the present crossed-beam experiments we studied the nonreactive scattering of Al(2P1/2) atoms with the collisions of O2 molecules at high collision energies ranging from 6.4 kcal/mol to 14.8 kcal/mol. We successfully achieved kinetic cooling of Al atoms with approximately 0.9±0.2 K in the laboratory frame, facilitated by the vibrational excitation of O2 (

$ v' $ = 1). The angular distributions of Al(2P1/2) scattering atoms exhibited the strong backward scattering with the production of vibrationally excited O2, indicating an end-on collision mechanism occurring along repulsive neutral surface.

Crossed-Beam Studies of Aluminum Atom Cooling via Inelastic Collisions with O2 Molecules†

- Received Date: 01/04/2025

- Available Online: 27/10/2025

-

Key words:

- Crossed molecular beams /

- Time-sliced ion velocity mapping /

- Kinetic cooling /

- Energy transfer

Abstract: The pioneering works have demonstrated that the method of single collisions in crossed molecular beams is an important technique for achieving kinetic cooling of atoms or molecules in specific rotational states. In this study, we investigated the elastic and inelastic collisions between Al(2P1/2) metal atoms and O2 molecules at high collision energies in the range of 6.4–14.8 kcal/mol, utilizing the laser-ablation crossed beams in conjunction with time-sliced ion velocity map imaging technique. We observed kinetic cooling of Al(2P1/2) atoms with an upper-limit laboratory-frame root-mean-square velocity of 24±3 m/s, corresponding to a translational temperature of 0.9±0.2 K in the laboratory frame, facilitated by the vibrational excitation of O2 ($ v' $=1) in inelastic collisions. The translational cooling of Al atoms in the lab frame enhanced detection probability in the transformation of density-to-flux, as evidenced by the scattering images obtained during the experiments.

首页

首页 登录

登录 注册

注册

DownLoad:

DownLoad: