-

Copper (Cu) is an essential trace element in living systems, acting as a cofactor in diverse biological oxidation-reduction reactions and responsible for the formation of reactive oxygen species. Besides its vital role in massive oxidases and oxygenases [1], Cu plays crucial roles in diverse metabolic pathways and forms dynamic complexes with amyloid peptides. These Cu-peptide interactions have been implicated in the pathogenesis of several severe disorders, including Alzheimer disease, diabetes mellitus, and cancer, as well as in copper homeostasis diseases (Menkes disease and Wilson disease) [2−6]. In the proteins associated with these diseases, histidine (His) residues play essential roles in Cu coordination, highlighting their critical physiological functions and therapeutic potential [7−9].

Cu(II)-His species are present in a wide range of enzymes, such as blue copper proteins and other copper proteins, where they regulate catalytic activity [1, 10, 11]. These species are also found in the N-terminal binding motifs, which have been implicated in DNA cleavage and shown to exhibit antitumor activity [12, 13]. Since the discovery of such species in human blood, extensive research has focused on elucidating the static and dynamic coordination geometry of Cu(II) in His-containing peptides and proteins [14−18]. For instance, the ATCUN/NTS (amino-terminal copper and nickel/ N-terminal site) motif glycylglycyl-L-histidine (GGH) forms mononuclear Cu(II) complexes via coordination with the N-terminal amino nitrogen (N), two deprotonated amide N and the imidazole N of the His residue. In contrast, L-histidylglycine (HG) binds Cu(II) through its N- and C-termini and an amide O, with the His residue excluded from the Cu(II) coordination sphere [19]. Although the low pKa of His initially suggested it as the primary Cu(II) binding site [20, 21], the distinct coordination geometries observed in GGH and HG reveal that steric effects imposed by His crucially influence donor group selection [22]. However, the extent of these steric constraints on Cu(II)-peptide remains poorly understood.

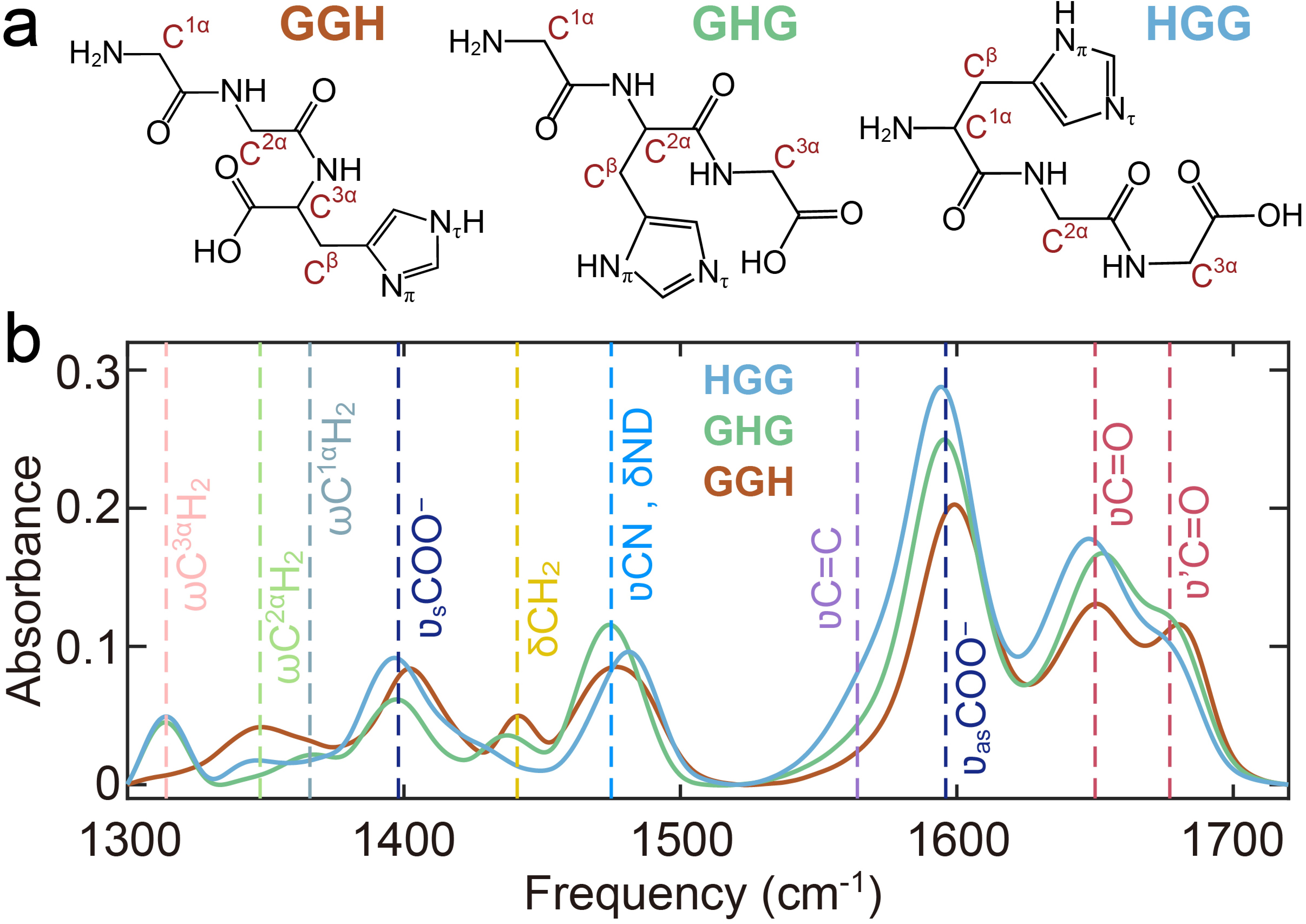

In this work, we investigated the pH-dependent Cu(II) coordination of three tripeptides, GGH, glycyl-L-histidylglycine (GHG) and L-histidylglycylglycine (HGG) (FIG. 1(a)). By systematically varying the position of the His residue from the N- to the C-terminus, we demonstrate dramatic shifts in Cu(II) coordination geometry and donor group involvement. Additionally, pH-dependent studies reveal that the protonated N-terminus serves as the initial Cu(II) binding site, highlighting its role in modulating the steric effects imposed by the His residue.

-

GGH, GHG, and HGG were obtained from Leon (Nanjing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (purity > 98%). Tris-HCl and MES salts (purity > 99%) were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology.

For IR spectroscopy, labile protons were exchanged with deuterons by dissolving peptides in D2O (Macklin Biochemical Technology) at ~2 mg/mL, followed by lyophilization (repeated twice). Experiments used deuterated solutions in 200 mmol/L Tris-DCl buffer, with pH adjusted using 1 mol/L DCl or 1 mol/L NaOD and verified with a Thermo Scientific Orion 9810BN pH meter. Unless otherwise specified, Cu(II)-tripeptide complexes were prepared at a 1:1 molar ratio.

-

UV-Vis spectra were recorded on an INESA L9 spectrophotometer (1 nm resolution, 290–1000 nm) using a 1 cm quartz cuvette. Samples contained 2 mmol/L Cu(II)-GHG/HGG (1:1 molar ratio with CuCl2), with pH adjusted as above.

-

FTIR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Invenio-S sptrometer (room temperature). Samples (~10 mg/mL peptide in 200 mmol/L Tris-DCl, pH 7) were placed between CaF2 windows (50 μm Teflon spacer). Cu(II)-tripeptide complexes (1:1 molar ratio) were prepared in the same buffer.

-

The instrumentation and methods for acquiring 2D IR spectra have been described previously. Briefly, the mid-IR pulses (~19 μJ, 50fs, 1kHz) were split to the probe (k3) pulse and pump pulses (k1 and k2) using a CaF2 wedge and two 50:50 CaF2 beam splitters. Two delay stages (ANT95L, Aerotech) were employed to control the time delays between k1, k2 and k3, namely τ1 and τ2. The stationary k2 beam was chopped at a frequency of 500 Hz to isolate the pump-probe and 2D IR signals from the large transmitted k3 background. The nonlinear signal was collected at a fixed waiting time τ2=150 fs as a function of evolution time τ1, scanned in 4 fs steps up to 2000 fs, using a 2×32 pixel MCT detector connected to an integrator (FPAS 6416, Infrared Systems Development). The sample was held between two 1 mm CaF2 windows separated by a 50 μm Teflon spacer in a temperature-regulated brass jacket.

-

EPR measurements were carried out on a Bruker A200 spectrometer operating at an X-band (9.32 GHz). The sample is liquid, loaded into an 80 μL quartz capillary tube and tested at a temperature of 100 K. The experimental parameters were set as follows: 5.01 mW microwave power, 2 G modulation amplitude, 100 kHz modulation frequency, 40.96 ms time constant. 3 mmol/L Cu(II)-GHG sample was prepared by mixing standard solutions of CuCl2 and GHG in 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer. Cu(II)-HGG at the same concentration (3 mmol/L) was prepared in water to avoid interference by buffer salts.

-

1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with 5 mm QCI cryoprobe. Samples (2 mg/mL Cu(II)-GHG in D2O, 1000:1 GHG:Cu(II) molar ratio) were referenced to residual HOD (δ 4.7 ppm).

-

GGH serves as a key model system for studying amide linkages, with its vibrational modes well-characterized by IR and Raman spectroscopy [19, 23−25]. In the IR spectrum of GGH (FIG. 1(b)), the amide I vibration displays two absorption bands at 1647 and 1679 cm−1 at neutral pH, corresponding to the C-terminal (

$\nu$ C=O) and N-terminal ($\nu^\prime$ C=O) amide carbonyl stretch, respectively. This frequency difference arises from the deprotonated C-terminus and protonated N-terminus. The position of the His residue further influences these bands, inducing shifts in frequency and intensity. The C-terminal carboxylate (COO−) exhibits asymmetric ($ \nu_{\rm{as}} $ COO−, 1595 cm−1) and symmetric stretch ($ \nu_{\rm{s}} $ COO−, 1402 cm−1) stretching mode. A shoulder band near 1570 cm−1 corresponds to the imidazole C=C stretch ($ \nu $ C=C) of the His residue.Upon deuteration, the amide II band (a combination of CN stretch

$ \nu $ CN and NH in-plane bend$ \delta $ NH) shifts to 1465–1490 cm−1. Notably, the$ \nu_{\rm{s}} $ COO− band of GGH is blue-shifted compared to HGG and GHG, attributed to hydrogen bonding between the COO− group and the His residue [19]. This interaction also shifts$ \nu_{\rm{s}} $ COO− band from 1396 cm–1 to 1402 cm−1 and eliminates the shoulder band at 1408 cm−1, due to restricted COO− torsional motion [23, 26]. Other vibrational bands, observed in the region below 1465 cm−1, arise from α-carbon methylene wagging ($ \omega $ CΗ2) and bending ($ \delta $ CH2) modes [26, 27], as labeled in FIG. 1(b). -

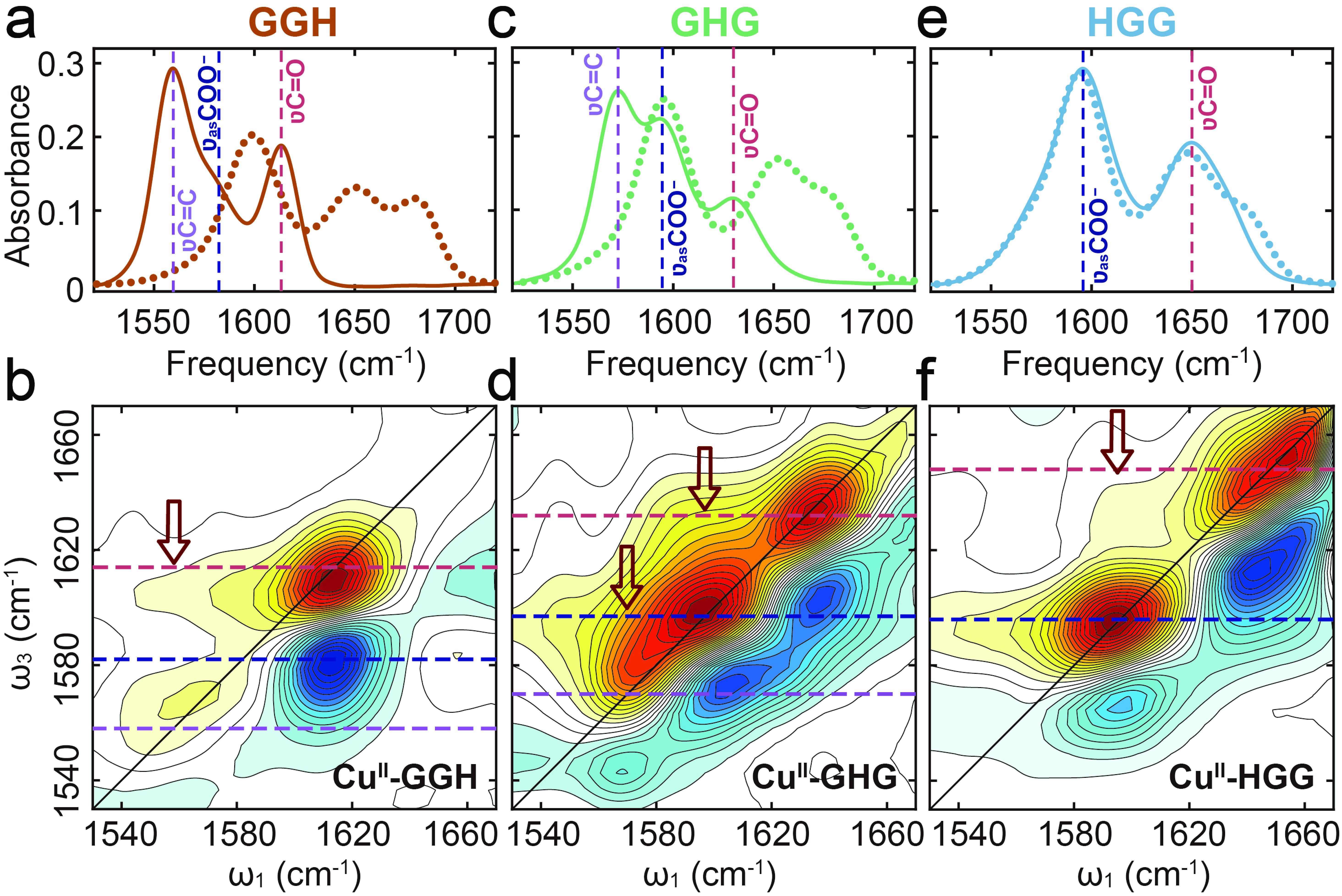

While the IR spectra of GGH, GHG and HGG showed considerable similarity in the region of 1530−1700 cm−1, their Cu(II) complexes exhibited significant differences (FIG. 2), revealing that substantial influence of His residue positioning on Cu(II) coordination geometry. Previous studies have established that Cu(II) coordination to imidazole nitrogen induces marked changes in the His

$ \nu $ C=C band (~1569 cm−1) [19, 28, 29]. At neutral pH, GGH coordinates Cu(II) through four donor atoms from amino, imidazole, and deprotonated amide groups [16], resulting in a pronounced$ \nu $ C=C band shift to 1558 cm−1 ((FIG. 2(a)). This characteristic feature was observed in the spectrum of Cu(II)-GHG (FIG. 2(c)) but absent in the spectrum of Cu(II)-HGG (FIG. 2(e)), indicating that the imidazole group in HGG did not participate in Cu(II) coordination.GGH chelates Cu(II) through its deprotonated amide nitrogen [30], resulted in a significant shift of the

$ \nu $ C=O band to 1615 cm−1 (FIG. 2 (a) and (b)). Although the GGH C-terminus does not serve as a ligating site, the formation of Cu(II)-GGH still affects the$ \nu_{\rm{as}} $ COO− band, shifting its peak frequency from 1596 cm–1 to 1584 cm−1 [19]. Observation of cross-peaks at ω1/ω3 = 1558/1615 cm−1 but not at ω1/ω3 = 1558/1584 cm−1 (FIG. 2(b)), confirms that imidazole ring and deprotonated amide group share the same Cu(II) coordination sphere, which left the C-terminus out.In contrast to GGH, GHG showed smaller frequency shifts upon Cu(II) coordination (FIG. 2 (c) and (d)). The broadened

$ \nu_{\rm{as}} $ COO− band and red-shifted$ \nu $ C=O band (1632 cm−1) suggested partial amide deprotonation, supported by the relatively preserved amide II band intensity (FIGs. S1 and S2 in Supplementary materials, SM). Cross-peaks observed at ω1/ω3=1570/1697 cm−1 and 1597/1632 cm−1 indicated coordinated participation of His residue, deprotonated amide, and C-terminus (FIG. 2(d)).HGG displayed minimal in the amide I/II band changes (FIG. 2(e) and FIG. S3 in SM), indicating unfavorable amide nitrogen deprotonation. The broadened

$ \nu_{\rm{as}} $ COO− band (FIG. 2(e)) and cross-peak observed at ω1/ω3=1596/1648 cm−1 (FIG. 2(f)) revealed exclusive coordination through C-terminus and amide oxygen. These observations demonstrate that the His residue in HGG imposes steric constraints that influence initial complex formation and inhibit amide deprotonation [22]. This steric effect aligns with observations in HG and leucine-containing peptides [19, 31, 32], underscoring the critical role of side-chain positioning in metal coordination chemistry. -

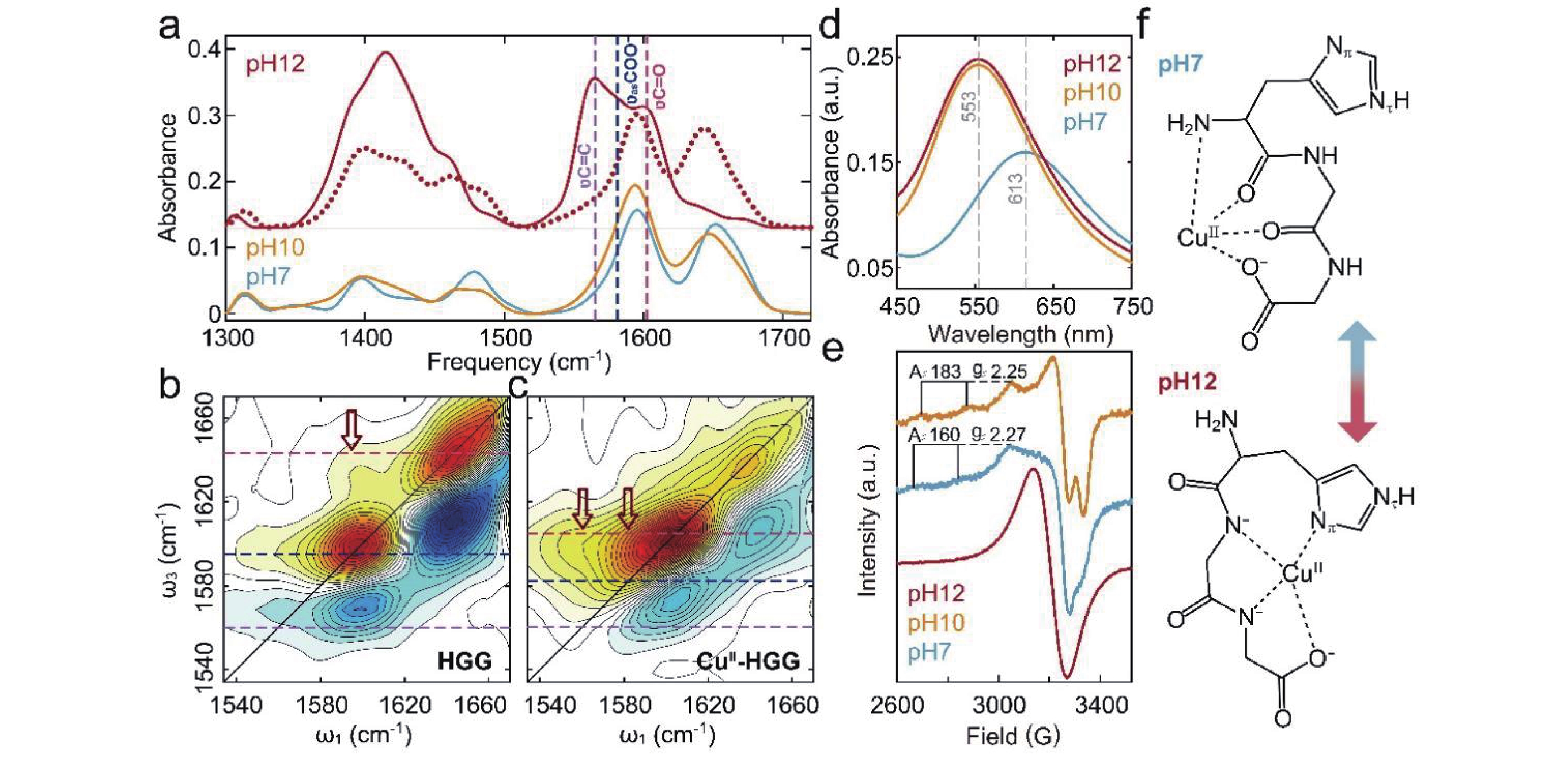

To elucidate the role of the histidyl residue in Cu(II) coordination, we examined pH-dependent structural changes in Cu(II)-HGG complexes using FTIR, 2D IR, UV-Vis, and EPR spectroscopies (FIG. 3). Increasing pH from 7 to 10 induced a red shift of the amide I band and an intensity drop of the amide II band (FIG. 3(a)), consistent with amide hydrogen substitution by Cu(II). At pH 12, the amide I band intensity dropped sharply, while three new bands emerged at 1560, 1582, and 1605 cm−1. The emergence of 1560 cm−1 band confirmed His residue coordination to Cu(II). The significant frequency shift of amide I band from 1643 cm−1 to 1605 cm−1 (FIG. 3(a)) and

$ \nu_{\rm{as}} $ COO− band from 1596 cm−1 to 1582 cm−1 (FIG. S4 in SM), indicated amide deprotonation.2D IR spectroscopy provided critical insights into the pH-dependent coordination changes of Cu(II)-HGG. At pH 12, comparison of HGG (FIG. 3(b)) and Cu(II)-HGG (FIG. 3(c)) spectra revealed significant geometric variations. N-terminus deprotonation shifted the

$\nu'$ C=O band, yielding a consolidated amide I band at 1643 cm−1 (FIG. 1(b) and FIG. 3(a)). The cross-peak at ω1/ω3 = 1595/1643 cm−1 (FIG. 3(b)) confirms persistent C-terminus/amide hydrogen bonding. However, Cu(II) introduction generated a new cross-peak at 1560/1582 cm−1 while diminishing the 1595/1643 cm−1 signal (at pH 7, FIG. 2(f)), demonstrating a coordination shift from amide O to deprotonated amide N. The characteristic ridge at ω3 = 1582 cm−1 and broad$ \nu $ C=C band further indicates imidazole Nπ/Nτ participation in Cu(II) binding.Complementary UV-Vis and EPR studies validated these coordination changes. The observed blue-shift of the d-d transition band of Cu(II) to 585 nm (FIG. 3(d)) matches the predicted wavelength for N-rich (deprotonated amide/imidazole) coordination [22]. EPR spectra (FIG. 3(e)) exhibits nitrogen hyperfine splitting, confirming multiple N-donor ligands at pH 12 [16].

These results establish the N-terminus protonation state as a critical modulator of Cu(II) coordination geometry. Under neutral conditions, binding initiates at the protonated N-terminus (FIG. 3(f)), which prevents Cu(II) hydrolysis before progressing to amide O coordination. His-induced steric hindrance restricts amide deprotonation, ultimately favoring 1N3O coordination (N-terminal amino N and 3 O donors). At pH 12, N-terminus deprotonation triggers a complete rearrangement: Cu(II) first coordinates the C-terminal amide N, then sequentially incorporates adjacent amide N and imidazole N donors, yielding 3N1O coordination.

-

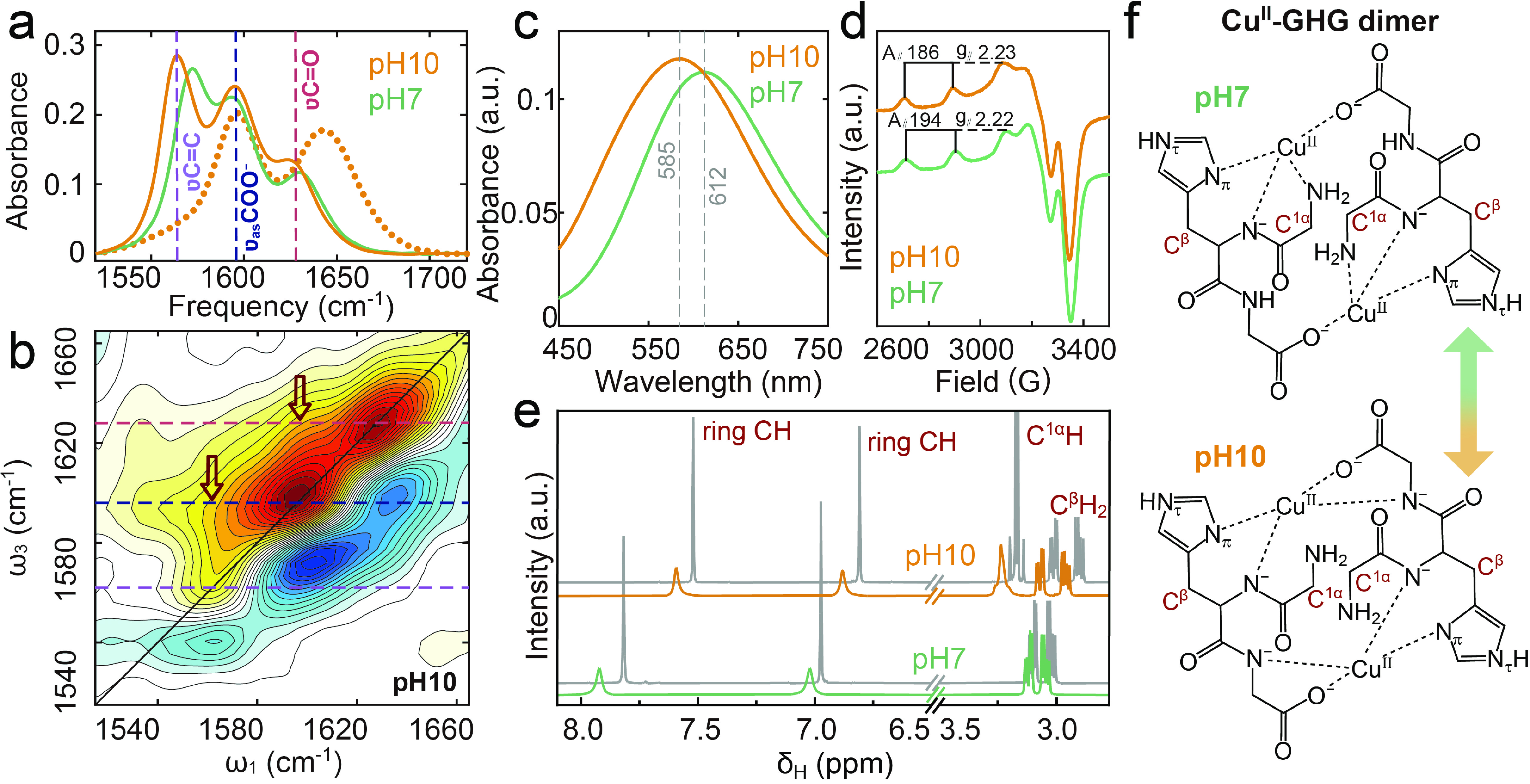

Our comprehensive spectroscopic analysis of Cu(II)-GHG (FIG. 4) reveals a pH-dependent coordination mechanism. At neutral pH, Cu(II) preferentially binds to the protonated N-terminus, while increasing pH to 10 induces complete N-terminus deprotonation, as evidenced by the disappearance of the

$ \nu^\prime $ C=O band (~1670 cm−1, FIG. 4(a)). This transition triggers three key coordination changes: (1) red-shifted$ \nu $ C=O (amide) and$ \nu $ C=C (imidazole) vibrational bands (FIG. 4(a)); (2) altered 2D IR patterns (FIG. 2(d) and FIG. 4(b)) indicating increased amide N coordination through hydrogen substitution; and (3) UV-Vis λmax shifts (FIG. 4(c)) showing amino N replacement by deprotonated amide N while maintaining 3N1O geometry, which was further confirmed by the EPR spectra (FIG. 4(d)). NMR studies reveal persistent His and N-terminal amide coordination (FIG. 4(e)), with additional C-terminal amide involvement at pH 10 evidenced by C3αH2 signal shifts (FIGs. S5 and S6 in SM).These results establish a pH-dependent coordination mechanism for Cu(II)-GHG complexes (FIG. 4(f)). At neutral pH, Cu(II) forms a binuclear dimeric complex through coordination with four sites: (1) a deprotonated amide group, (2) the imidazole ring of His residue, and (3) both N- and C-termini. As pH increases to 10, N-terminus deprotonation weakens Cu(II)-amino N bonding, inducing structural rearrangement. This transition involves Cu(II)-mediated amide hydrogen substitution at the C-terminal amide group, while maintaining the characteristic 3N1O coordination geometry.

-

Our findings demonstrate that both the protonation state of the N-terminus and the steric influence of His residue critically determine Cu(II) coordination geometries in peptides. At physiological pH, Cu(II) binding initiates at the protonated N-terminus before extending to adjacent amide groups. While backbone flexibility in GGH and GHG permits the transition from amide O to deprotonated amide N coordination, the His residue of HGG imposes steric constraints that prevent amide deprotonation, resulting in a distinctive 1N3O coordination sphere (one amino N, two amide O, and one carboxylate O donors) that excludes His participation. However, N-terminus deprotonation at elevated pH induces complete reorganization to a 3N1O geometry comprising two deprotonated amide N, one imidazole N, and one carboxylate O. This pH-dependent transition mechanism is conserved across peptides, as evidenced in GHG complexes where increasing pH from 7 to 10 shifts coordination from the N-terminus to a C-terminal deprotonated amide group, highlighting the essential role of N-terminus as both an initial metal anchor and structural regulator that prevents Cu(II) hydrolysis during coordination establishment.

Supplementary materials: FTIR and NMR spectra of tripeptides and their Cu complexes.

The Critical Role of Histidine in Copper (II) Coordination†

- Received Date: 30/04/2025

- Available Online: 27/10/2025

-

Key words:

- 2D IR spectroscopy /

- Histidine-containing peptide /

- Copper coordination

Abstract: Histidine (His), as the most chemically active and versatile member among the 20 natural amino acids, plays a key role in the coordination of copper (II) (Cu(II)) in biological systems. Cu(II)-His species are ubiquitous in metalloenzymes and proteins associated with various neurodegenerative diseases, where they regulate catalytic activity and mediate intracellular copper transport. While the steric influence of His is known to dictate donor group selection in Cu(II) coordination, the extent of these constraints on peptide complexes remains unclear. In this study, we employed a multi-spectroscopic approach (FTIR, 2D IR, UV-Vis, EPR, and NMR) to systematically investigate pH-dependent Cu(II) coordination in three tripeptides. Our results demonstrate that Cu(II) coordination geometries are cooperatively determined by both the protonation state of the N-terminus and the steric constraints imposed by the His residue.

首页

首页 登录

登录 注册

注册

DownLoad:

DownLoad: